Congress Vienna. To understand European history it’s hard to ignore the Congress of Vienna. For 10 months, Vienna became the center of the world thanks to this historic event. This overview lays out the objectives, participants and the outcome of the congress of 1814/1815.

Significance

Briefly put, the Wiener Kongress was one of the most significant international political summits in Europe.

Briefly put, the Wiener Kongress was one of the most significant international political summits in Europe.

After the Congress of Vienna re-conciled the multiple conflicts of interest between the European powers it created a period of almost 40 years without major European wide conflicts. On a negative note, the summit resulted in a deliberate step back in history: It was going against the French Revolution and all its democratic, egalitarian and liberal ideals. In a way, it kick started the Pre-March Period (Vormärz) which eventually led to the revolution in March 1848.

On a more mundane note, the Congress was a cultural Olympiad without comparison. For ten months, Vienna entertained more than 200 delegates from all over Europe with a marathon cultural calendar: from daily balls and society events to catering to the vanities of its top guests. From this time onwards, Viennese balls and waltz dancing gradually rose to international fame.

Specifically, the Wiener Kongress played a pivotal role in anchoring Vienna’s image as a society of Vienna waltz dancing, cake eating bohemiens who love life and women, and who use their culture to outwit their European fellows. Prince Charles de Ligne’s famous words:

Until this day, some of the best Vienna balls play to this tradition of uniting politicians and society people from across the world. Although their political power today is negligible.

Who Hosted the Vienna Congress 1815?

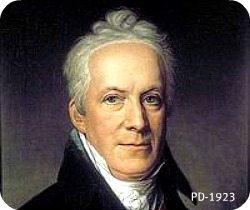

Officially, Austrian Emperor Francis I hosted the Vienna Congress in 1814 and 1815. However, Austrian chancellor Prince Metternich presided the Congress of Vienna and played a key role in the difficult negotiations among the Great Powers, especially with France.

Background

After years of raging war, Napoleon Bonaparte had left Europe in shatters. While he was in exile on the Italian island of Elba, the European state system needed re-structuring. The First Treaty of Paris (Erster Pariser Frieden) established a congress in Vienna where all participants of the war would decide on a substantial political re-order in post-war Europe. Vienna as the epicentre of the Central European Habsburg Empire with its vast territories and regional interests, seemed an obvious choice. In September 1814, about six months after the fall of Napoleon, Habsburg Emperor Francis I invited the European rulers and their key diplomats to the Congress of Vienna.

Objectives of The Congress of Vienna

Essentially, the Congress of Vienna was about

- re-installing the absolutistic monarchies in Europe before the French Revolution of 1789, also known as the Restauration

- legitimising the ruling monarchies and fiefdoms

- re-structuring Germany’s internal affairs

- weakening France’s political power

- creating rules for mediating and managing conflicts among European rulers in a peaceful way.

It was not about the peoples and their needs for freedom and prosperity, but of restoring the interests of the old European dynasties.

Where In Vienna Did The Congress Take Place?

During the Congress of Vienna most of the political meetings took place at the Palace on Ballhausplatz, which is part of Hofburg Palace. Today, it houses the Federal Chancellor’s office (Bundeskanzleramt).

Participants Of The Congress of Vienna

Through their heads of state and senior diplomats the five European super powers Russia, Great Britain, Prussia, Austria and France took part at the Congress of Vienna. In addition, the other German courts, previously sovereign cities, Switzerland and other European states sent delegates to Vienna. All in all, approximately 200 rulers and their diplomats flocked to the Austrian capital.

Austrian Empire

Emperor Francis I: Although Franz I. detested Napoleon Bonaparte he agreed to the marriage between Napoleon and his own daughter Marie Louise in 1810. His subsequent alliance with Napoleon against Russia ended in defeat. However, the Treaty of Paris of 1814 boosted Francis’ I territorial powers. He came to rule the largest territory the Habsburgs and their predecessors had ever possessed.

Prince Metternich: Metternich noted: “The first and foremost objective of our Government’s endeavours, and that of all allied Governments since the restoration of Europe’s independence, is to maintain the existing order, which is the fortunate result of this restoration.”

Prince Metternich: Metternich noted: “The first and foremost objective of our Government’s endeavours, and that of all allied Governments since the restoration of Europe’s independence, is to maintain the existing order, which is the fortunate result of this restoration.”

Metternich was also interested in strengthening France’s role in Europe and use it to counterbalance Russia’s power.

His repressive politics worked for more than 30 years. However, for Metternich, 1848 (the year of the revolution) finally put an end to them.

Russia

Tsar Alexander I Pawlowitsch: was educated based on Rousseau’s liberal ideas, but was a weak and inconsistent ruler. At the Congress of Vienna, he promoted peaceful collaboration and order, obtained the neutral status of Switzerland and provided his new Polish territory with a liberal constitution. He invented the idea of the Holy Alliance.

Tsar Alexander I Pawlowitsch: was educated based on Rousseau’s liberal ideas, but was a weak and inconsistent ruler. At the Congress of Vienna, he promoted peaceful collaboration and order, obtained the neutral status of Switzerland and provided his new Polish territory with a liberal constitution. He invented the idea of the Holy Alliance.

Karl Robert (Vassilievich) Count Nesselrode: was the leader of the Russian delegation at the Vienna Congress. He turned into one of the most fervent promoters and defenders of the Holy Alliance.

Great Britain

Lord Henry Robert Stewart Castlereagh: was like Prince Metternich a strong conservative who detested Napoleon’s liberal ideas. Together with Metternich and Prince Talleyrand, he formed an alliance against Russia and Prussia. As a result, Russia won large parts of Poland. Prussia lost significant territories of Saxonia.

Lord Henry Robert Stewart Castlereagh: was like Prince Metternich a strong conservative who detested Napoleon’s liberal ideas. Together with Metternich and Prince Talleyrand, he formed an alliance against Russia and Prussia. As a result, Russia won large parts of Poland. Prussia lost significant territories of Saxonia.

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington: was British diplomat in France and of British-Irish origin. He took over the negotiations at the Vienna Congress from Lord Castlereagh on 1st February 1815. He later led the coalition army in the battle of Waterloo which ended nine days after the official end of the Congress.

Prussia

Karl August Prince of Hardenberg: State Chancellor of Prussia, one of the leading state reformers of the 19th century, liberal mind and promoter of democratic principles with the monarchy. At the Congress of Vienna, he managed to achieve equal status for Prussia and re-position it among the leading European Powers.

Karl August Prince of Hardenberg: State Chancellor of Prussia, one of the leading state reformers of the 19th century, liberal mind and promoter of democratic principles with the monarchy. At the Congress of Vienna, he managed to achieve equal status for Prussia and re-position it among the leading European Powers.

Wilhelm von Humboldt: one of the most famous German scientists, liberal reformer of the German educational system. At the Congress of Vienna, he successfully promotes Jewish civil rights but but is defeated in his objectives to create a liberal constitution for the German Bund.

France

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord: was the leader of the French delegation. He almost managed to position the defeated France as an equal negotiation partner at the Congress of Vienna. Napoleon Bonaparte’s escape from Elba and France’s defeat in the battle of Waterloo, however, thwarted his efforts.

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord: was the leader of the French delegation. He almost managed to position the defeated France as an equal negotiation partner at the Congress of Vienna. Napoleon Bonaparte’s escape from Elba and France’s defeat in the battle of Waterloo, however, thwarted his efforts.

Treaty Of Vienna

On 9 June 1815, the five signatory states signed the Treaty of Vienna. You can see the newly created territories and their boundaries in the historic map above. The battle of Waterloo was still raging on, ending in Napoleon’s defeat nine days later.

The vast majority of territories was re-distributed to the Great Powers as before the Napoleonic Wars. The big winner, however, was Russia, which obtained large parts of the Duchy of Warsaw (Poland). Germany was not successful in pushing through its aim to create a united German state. Austria received large territories in Italy, including Dalmatia, Friulia, Istria, Lombardia, and Venetia; and re-obtained regions such as Croatia, Upper Carinthia, Salzburg, Tyrol, Vorarlberg, and Galicia (Poland). On the other hand, it had to resign from its territories in Brisgau and the Austrian Netherlands. Switzerland was structured into 22 cantons and obtained neutral status. Sweden lost Finland and Swedish-Pommern but was acknowledged its Norwegian territories.

The Congress of Vienna was considered a big success. (See this animated map for further illustraion.) It had achieved its main aim, to re-create a balance of power in Europe pre-Napoleon. Friedrich von Gentz, Prince Metternich’s secretary of state, summarised: “…The task of this Congress was difficult and complicated. It was about restoring everything that 20 years of disorder had destroyed, re-constructing the political system from the large ruins with which a terrible tremor had covered Europe’s soil. […] This big task is accomplished. As they part today, the Sovereigns have committed themselves to one single, simple and holy obligation: that of deferring all other considerations in relation to peace keeping and of nipping in the bud every plan of destroying the existing order, with all available means.”

Following the battle of Waterloo, France ended up loosing key territories and was forced to pay 700 million Francs of indemnity and return the European art treasures stolen by Napoleon.

As the Ottoman Empire was excluded from the Vienna Congress, the internal grievances caused by the existing rulers were not taken into consideration

Other key achievements included the proscription of slave trade, and free international stream navigation.

The Holy Alliance (Heilige Allianz)

Based on an idea of Tsar Alexander I, Austria, Prussia and Russia formed a reactionary league in September 1815 in Paris. The Alliance aimed at suppressing all liberal movements and calls for constitutions by its peoples. The absolutistic monarchies of Austria and Prussia co-ordinated strict censorships and police interventions to suffocate calls for people’s rights right from the start.

The German Bund

Prince Metternich opposed the complete restoration of the German Empire. The new German Bund was a loose system of 35 sovereign states and four independent cities. Breaking up the German Empire meant that there was no single strong power: no single ruler, no common administration, military or jurisdiction. Emperor Francis I refused suggestions from sovereigns of small and mid-sized German states for the Austrian Empire to preside the German Bund. Instead, Austria led the German Bund as an executive branch until 1866.

more about key milestones in Vienna History

explore other essentials of Vienna Tourism

back to Vienna Unwrapped homepage